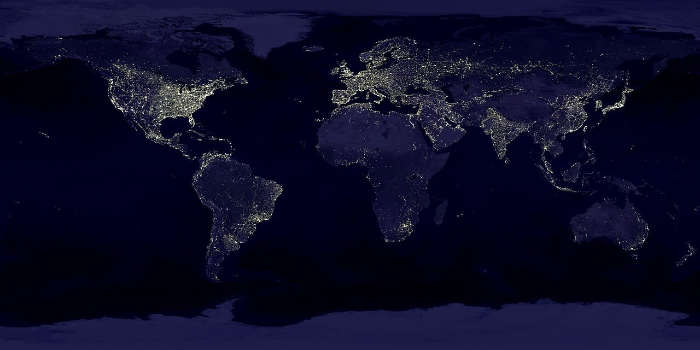

Sharia Law Countries 2026

Classic

Classic (some territories)

For Muslims Only

Mixed

Type of Sharia Law

Country | Type of Sharia Law↑ | |

|---|---|---|

| Pakistan | Classic | |

| Egypt | Classic | |

| Iran | Classic | |

| Sudan | Classic | |

| Iraq | Classic | |

| Afghanistan | Classic | |

| Yemen | Classic | |

| Morocco | Classic | |

| Saudi Arabia | Classic | |

| Somalia | Classic | |

| Mauritania | Classic | |

| Qatar | Classic | |

| Maldives | Classic | |

| Brunei | Classic | |

| Indonesia | Classic (some territories) | |

| Nigeria | Classic (some territories) | |

| Malaysia | Classic (some territories) | |

| United Arab Emirates | Classic (some territories) | |

| India | For Muslims Only | |

| Ethiopia | For Muslims Only | |

| Philippines | For Muslims Only | |

| Tanzania | For Muslims Only | |

| Thailand | For Muslims Only | |

| United Kingdom | For Muslims Only | |

| Kenya | For Muslims Only | |

| Myanmar | For Muslims Only | |

| Uganda | For Muslims Only | |

| Ghana | For Muslims Only | |

| Sri Lanka | For Muslims Only | |

| Israel | For Muslims Only | |

| Singapore | For Muslims Only | |

| Eritrea | For Muslims Only | |

| Bangladesh | Mixed | |

| Algeria | Mixed | |

| Syria | Mixed | |

| Mali | Mixed | |

| Jordan | Mixed | |

| Libya | Mixed | |

| Lebanon | Mixed | |

| Palestine | Mixed | |

| Oman | Mixed | |

| Kuwait | Mixed | |

| Gambia | Mixed | |

| Bahrain | Mixed | |

| Djibouti | Mixed | |

| Comoros | Mixed |

Sharia law is the set of rules and guidelines followed by people who adhere to the Muslim faith. These laws are derived from multiple sources, primarily the Muslim holy book, the Qur’an, and the sayings of the prophet Muhammad collected in another written record called the hadith. Sharia, which is alternately spelled Sharīʿah, has multiple similar translations, including “the correct path” and “the path leading to the watering place.” Sharia law is widely practiced among the Muslim countries of Africa and the nations of the Middle East, who believe it is God’s will for mankind. Sharia is interpreted by Muslim scholars, who then translate it into the fiqh, which is the body of Sharia law. Sharia law includes guidance applicable to all aspects of life, including public behavior, personal behavior, and even spiritual beliefs.

The Five Classifications of Sharia Law

Under Sharia law, all human actions are placed into one of five various categories, alternately known as “the five decisions” (al-aḥkām al-khamsa): obligatory, recommended, permitted, disliked, or permitted.

- Farḍ (or farīḍah or fardh, sometimes wajib) actions are obligatory or mandatory. These illustrate the fact that Sharia Law determines the things one absolutely should do in addition to outlining what one should not do. These duties are further broken into two sub-categories. Individual duties such as salat (daily prayer), which each person must perform for themselves, and community-wide duties such as janaza (funeral prayer), which do not require the participation of every individual member so long as the task is accomplished.

- Mustahabb actions are recommended actions that aren’t necessarily required, but which can be spiritually beneficial (in this world or the next) if performed. There are thousands of mustahabb acts, from as-salamu alaykum, a greeting, to sadaqah, a type of voluntary charitable donation.

- Mubah actions are permitted, neutral or indifferent. Mubah acts are neither mandatory nor forbidden and neither encouraged nor discouraged. They invoke no judgment, reward, or punishment from God. This is the largest category of actions.

- Makruh actions are disliked, abhorred, and looked down upon … but not expressly forbidden. Though these acts are not punished, those who refrain from them will be rewarded. Makruh acts may include behaviors such as eating garlic before attending mosque, swearing, or slaughtering an animal for food in view of other animals of the same species.

- Haram actions are forbidden or prohibited by God, usually in the Qur’an, and are considered sinful. Haram acts should never be performed, even if it is for an honorable cause. There are multiple points of view regarding which acts are and are not haram. Note too that this term should not be confused with the Arabic word haram, which means “sanctuary.”

Major Schools, or madhhabs, of Sharia Law

Nations that follow Sharia law are invariably Muslim majority countries, and each has its own interpretation of the various intricacies of the laws. As a result of these differences of interpretation, nations are rarely exactly in sync in what is allowed, what is forbidden, and what the consequences should be for engaging in forbidden actions. There are, however, a number of popular and well-respected schools of interpretation, called madhhabs:

- The Hanafi school - Considered the most liberal of the schools, with the strongest focus on reason and analogy. Favored by Sunnis in several countries, including India, Turkey, China, and Egypt.

- The Hanbali school - The most conservative (and to many Western onlookers, restrictive) of the schools. The rulers of Saudi Arabia, as well as the Taliban who reclaimed control of Afghanistan in 2021, adhere to the teachings of this school.

- The Ja’fari school - Another school that focuses upon reason. Favored by the Shiites in Iran; Iraq; and parts of Lebanon, South Asia, and Saudi Arabia.

- The Maliki school - This school is unique in the way it incorporates the interpretations of the people of 7th-century Medina, where the prophet Mohammed lived at one time. Favored by Muslims in much of North and sub-Saharan Africa.

- The Shafi’i school - Unique in the way it assigns a hierarchy to the various sources it pulls from, with the Qu’ran first, followed by the Sunna, scholars, and analogy/stories. Favored in Brunei, Malaysia, Indonesia, Yemen, and parts of the Middle East.

Sharia Law and its Compatibility with Modern Society

Countries that follow the most conservative interpretations of Sharia law have come under fire in recent years due to what many observers, especially those in secular countries, believe are intrusive, restrictive, and at times even inhumane rules, particularly against females. Examples of such restrictions include barring women from getting an education, forcing women to wear restrictive burqa or niqab veils when leaving the home, and implementing arguably misogynistic laws surrounding the rape of women. Moreover, Sharia punishments can often seem archaic, even cruel. These include amputation of the hands as a punishment for theft, 100 lashes for those caught in adultery, and the stoning to death of those who turn away from Islam (the sin of apostasy). The burden of proof for such punishments is quite high, so most crimes are punished using much less severe methods. However, the continued possibility of such punishments is viewed by many observers as cause for concern.

Similarly, critics of Sharia law argue that it is overly rigid and incompatible with modern principles including democracy, women’s rights, LGBTQ+ rights, and guidelines outlined in the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Arguments supporting these criticisms often reference lines in the Qu’ran that could be interpreted as advocating spousal abuse and violence against non-Muslims, or point to events that seem barbaric to many modern observers. For example, a widely publicized case in 2002 found a Nigerian woman sentenced to be half-buried in sand and then stoned to death for the crime of having a child out of wedlock. The woman was acquitted on appeal, but not before the case garnered international attention and sparked considerable outrage among Muslims and non-Muslims alike.

Countries that Follow Sharia Law

Different countries implement Sharia law to different degrees. A few countries, such as Iran and Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, allow strictly conservative classic Sharia principles to shape the entirety of their legal system. These are the most demanding systems as well as the systems most likely to be viewed by observers as oppressive. Most Muslim countries instead opt for hybrid systems, in which Sharia laws inform certain parts of the legal code, but not others. For example, a country may base its family and criminal laws on Sharia beliefs, but not its corporate or business laws. Other mixed legal systems may create two separate family codes: A Sharia-based code for Muslims and a separate, secular code for non-Muslims. Finally, a few countries follow Sharia law in some parts of the country, but not in others. The table below is based upon the work of Professor Jan Michiel Otto of Leiden University Law School in the Netherlands, and also incorporates data from newer sources where available.